The drain of science: a call for action and the bridges we burned

Commercial academic publishing oligopolies are draining science. Beigel et al. (2025) call for community control, but the Lithuanian case shows this is difficult after dismantling domestic journal publishing infrastructure. We must restore trust in it first to regain sovereignty.

The “publish or perish” race is a fixture of academic life, even as studies periodically warn that we are approaching a dead end. Since the 1980s, we have referred to this as the “serials crisis,” usually pointing the finger at commercial publishers who profit immensely from the scientific system.

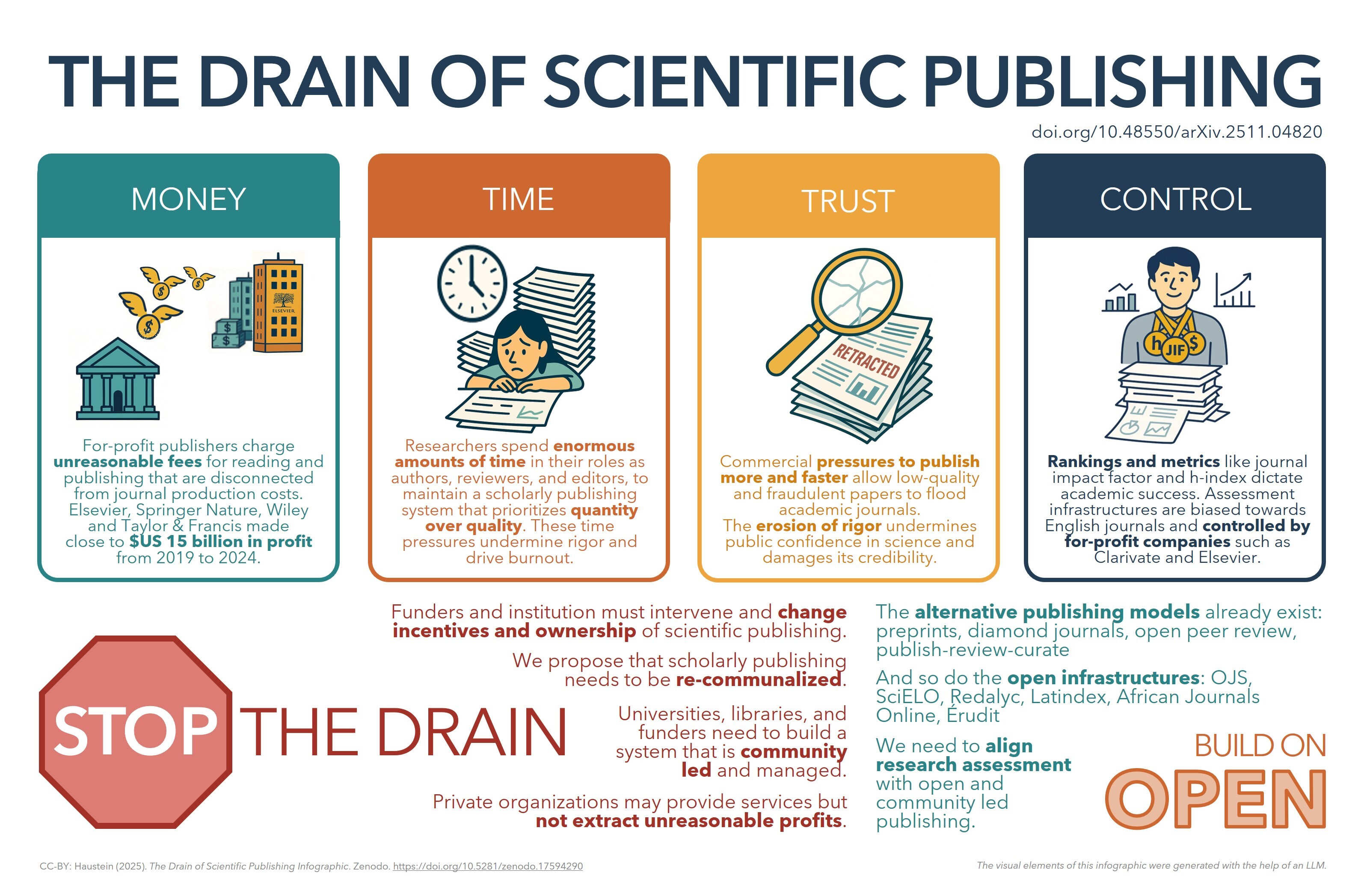

However, a recent study by Beigel et al., “The Drain of Scientific Publishing” (2025), takes a deeper look, visualising the concentration of commercial publishing and issuing a desperate call for the academic community to take publishing back into its own hands. Yet, as we will see, taking back control is not as simple as it sounds—especially in countries that have already burned bridges between their researchers and domestic journals.

The four-fold drain

In this widely discussed paper, Beigel et al. present a grim diagnosis: the current commercial publishing oligopoly acts as a massive pump, extracting life from the research ecosystem. They conceptualise this as the “Four-Fold Drain”:

- Money: Public funds, instead of supporting research infrastructure, flow into the pockets of private shareholders via exorbitant article processing charges (APCs). The profit margins of these major publishers consistently exceed 30 per cent.

- Time: We are trapped on a “treadmill of constant activity”. The number of papers published worldwide is growing exponentially, leaving researchers exhausted by the sheer volume of peer review and editorial processing required to sustain the system.

- Trust: The race for quantity breeds “paper mills” and fraudulent research, eroding the epistemic reliability of the scientific record.

- Control: Perhaps most dangerously, the academic community has lost sovereignty. Private corporations now own not just the journals, but the metrics and data that underpin global ranking and evaluation systems. For instance, Clarivate (owned by private equity) publishes the Journal Impact Factor (JIF), while Elsevier owns Scopus and an expanding arsenal of analytic platforms that capture the entire research lifecycle. Universities and funders blindly rely on these opaque commercial indicators to decide careers, funding, and competition in institutional rankings, forcing scientists to game the system instead of doing meaningful work.

The authors propose a radical solution: re-communalise publishing. They urge universities, libraries, and funders to build a system that is community-led and managed. By actively supporting federated open infrastructures and investing in community-based publication platforms and non-commercial journals, they argue, these institutions can ensure the system works to further research and education, not the market.

But can we go back? A tale of two strategies

If the solution is to return to community-led publishing, do we still have a community infrastructure to return to?

Here, I’d like to share insights from a comparative study I conducted with Eduard Aibar. We analysed how Spain and Lithuania responded to this global pressure for internationalisation, revealing that “taking back control” is impossible if you have already dismantled your own foundations.

Spain maintained a resilient domestic publishing infrastructure (autonomous coexistence) that is still visible in Clarivate data. Because their local university journals remained a viable option within Web of Science coverage, Spanish researchers could use new commercial players, such as MDPI and others mentioned by Beigel et al., merely as a “portfolio addition”—an extra tool, not a lifeline.

In contrast, Lithuania represents a cautionary tale about dependent displacement. Although local journals still exist, their presence within Lithuanian Web of Science outputs has been drastically diminished, falling from a peak of 52 per cent in 2008 to just 7 per cent by 2024. This collapse was not accidental; it was precipitated by specific policy measures, such as complex citation thresholds and “suspension lists,” which actively marginalised domestic outlets.

Lithuanian researchers, with local venues devalued and facing perceived gatekeeping in traditional Anglo-American journals, had nowhere to go but to new players. Consequently, Switzerland, home to MDPI, Frontiers, and others exploiting open access publishing, exploded to become the single largest destination for Lithuanian research, hosting 35 per cent of the total national output by 2022. MDPI alone accounted for nearly a third (31 per cent) of all papers, effectively functioning as a commercial “systemic substitute” for the dismantled national infrastructure.

The trap we built: the dual role of the elite

Why did Lithuania diminish its own infrastructure? Our research on multi-actor policy dynamics reveals that this wasn’t just a top-down mandate from clueless politicians. It was a complex dance involving the entire community.

On one side, portions of the academic elite and university administrations historically used local journals as “self-contained publishing machines”. These venues were often used to game the system by inflating citation counts and churning out papers to meet formal requirements without ensuring international quality.

Other members of the same elite, who served as advisors or policymakers in their own right, saw this manipulation. They attempted to reform the local system but faced strong resistance from the academic community and university rectors who lobbied to protect their interests. The state resorted to the only measure available: punitive measures against domestic journals. They implemented “insular policy feedback”, creating blacklists of suspended journals and effectively banning many local venues from high-level research assessment.

The result? A total collapse of trust. By trying to stop the gaming at home without fixing the underlying culture, policymakers drove our researchers into the arms of global commercial publishers. We then became passive donors to the international business of science, exporting our public funds to pay for APCs abroad or relentlessly working for this system because we no longer trusted our own journals.

The way forward: investment and revision

Paradoxically, the physical foundation still exists. According to the 2020 report by the Association of Lithuanian Serials which was the foundation for the following study, 225 small-scale scholarly journals are still published in Lithuania. The vast majority—nearly 80 per cent—are owned by state institutions such as universities and research centres and can be identified as state-owned journals.

We have the infrastructure that Beigel and colleagues dream of, but we are starving it. While the DIAMAS project—a European initiative aimed at supporting institutional publishers—is a promising step forward, these European funds have not yet effectively reached nations like Lithuania. Currently, our local journals are surviving on universities’ crumbs and the sheer dedication of editors. Many still operate on outdated infrastructure; for instance, one-third of these journals still rely on basic institutional websites rather than professional publishing platforms.

Lithuania is not alone in this predicament; it is merely a stark example of a challenge facing many nations that have sacrificed domestic capacity for global metrics. Thus, Beigel et al.’s call to action is directed to funders, policymakers, and university leaders who understand that simply pouring money into local journals is not enough: though investment is desperately needed to modernise our crumbling infrastructure, it must go hand-in-hand with a rigorous, honest revision of the national publishing ecosystem. We must root out the culture of gamesmanship and nepotism, raise standards to the international level, and—most importantly—rebuild the trust that we ourselves destroyed.

Only by restoring the integrity of our own domestic publishing ecosystems can we break the dependency on external validation. Once we trust our own community-led, transparent journals to define quality, we will no longer be forced to import prestige from commercial giants, effectively ending our status as hostages and reclaiming sovereignty over our science.

Fortunately, we do not have to invent everything from scratch: a wave of innovations, from open peer review and federated open infrastructures to new “publish, review, curate” models, is already on its way, ready for the academic community to adopt. The tools to rebuild our bridges are coming; we now need to show we have the courage to use them.

AI use disclosure: During the preparation of this post, I used artificial intelligence tools to analyse the draft for clarity and coherence. The AI tool provided suggestions to improve the flow of the text and identify ambiguous phrasing. I reviewed the options suggested and incorporated changes at my discretion; all original arguments, data, and final phrasing remain my own. The final version was polished by a human language editor who enhanced the wording and expressions. This disclosure statement was also drafted with the assistance of an AI tool.

DOI: 10.59350/g7vhc-swq32 (export/download/cite this blog post)

2 Comments

You can also take at my curated journal list. For certain fields only. Regularly updated. https://simonbatterbury.wordpress.com/2015/10/25/list-of-decent-open-access-journals/

My thoughts on all of this go back a few years. eg the OA Manifesto https://doi.org/10.21428/6ffd8432.a7503356 and https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/impactofsocialsciences/2020/10/24/publishing-articles-concerned-with-social-justice-issues-in-unjust-journal-outlets-seems-wrong-open-access-qa-with-simon-batterbury/ I appreciated your remarks since they highlight poor behaviors by academics, as well as the awful dominance of commercial publishers. The two are vital to address together. Of course the answer is to use the commercial publishers as little as possible, for senior staff to reward each other and especially junior staff for publishing in community journals, and also to train graduates in the necessity to think ethically about publication choices. It is really appalling that academics, some like me who work on critical and radical topics, continue to publish with unethical corporate publishers who a) charge too much b) pay their senior execs a lot and c) cripple our library budgets, if those can afford any deals with big publishers at all. In the anglophone countries we have been obsessed with journal and promotion metrics, which has frankly not privileged community journals (much better in Spain and Latin America). Few have been concerned with publication ethics really. [no AI used]

Add a comment